Game Architecture, Level Design, Game Design, Sound Design, Writing, Art

These are the first areas which likely require the greatest deal of constraint when discussing architecture in videogames. I say constraint because a single individual could, in any given game, be responsible for many or all of these. From a design perspective, such a thing is the very definition of a problem. Though architects of real objects eventually separated themselves from being the builders, and became the conceptual creators, the designers of built space, such a separation has not occurred for games, even in the slightest. Often a videogames is made by one or even a few individuals, and only in fairly large scale games are all these aspects of the game given to separate individuals to handle and given time to appropriately grapple with.

It is perhaps important to note this from the start because it is such an overlooked fact. Simply put, most design, most architecture, and most art in games is extraordinarily poor, due to its conglomeration onto individuals who have little specialization or understanding of how to deal with these important aspects when making a game. However, largely for the sake of argument and discussion, we also need to attempt to place where each role ends and where another begins, for the sake of understanding how these specializations are important to understanding the architecture of a game.

Game Architecture

First, understanding what architecture is as it relates to a game is different from understanding what architecture is as it relates to anything in the real world. Architecture in a game, unlike in the real world, is pure artifice. It is a construction based entirely on virtualization. Much of what might seem logical at first can simply be thrown out, ideal forms can be realized, structures can be built infinitely tall. Yet, inside of a videogame, there are intentional limits, the first and most obvious being that of the hardware. Despite being able to build a mathematically infinitely tall building, there is no hardware that could virtualize such a construction, and thus it is while possible, not practical or useful for the purpose of understanding architecture in games. It is however, what games may one day come to achieve, the impossible inside a realm of improbables.

And architecture is exactly thus, a suite of constructed impossibles inside a realm of improbables. Architecture is both art and mathematical minutiae, if the architect so desires, to explore spaces in impossible ways. In Dark Souls particularly, there are churches grander than anything on Earth, fortresses filled with tireless traps, and dilapidated gothic castles reminiscent of a once proud tradition. The architecture in games, more than anything else, lends itself to being a character first and plausible space secondarily. The character of the architecture in the game tells us a story about the place in which the player inhabits, and the story it tells is of immediate visual and visceral consequence, as interacting within the space gives way to immersion, should the space be validated in such a manner.

The architects job then, is to dream of a story for the space in which the player will inhabit, and to enliven it to the fullest degree possible through a use of space. It is a unique position, both similar and different to that of the artist, who may inhabit the world with perhaps more literal textures, giving the space a more unified feeling. Though an architect could go so far as to even construct the armor, the art, and the interests of characters in the world, oftentimes this is the separation between architect and game artist, in those studios where the two get to make such a rare distinction. The architect focuses on building the space and its story, while the artist will build the characters who inhabit the space. Such discussions are often close in terms of departments, simply due to the relative necessity of both working in tandem to fully realize a space.

Level Design

Here is likely a good place to start discussing level design, because if the architect is the one to construct the impossible spaces which the player must inhabit, the level designer’s responsibility is often to ground these constructions in a manner in which such spaces are navigable and intuitive. In a sense, the level designer’s responsibilities include the ability to ground the architect’s possible spaces into a playable space, into a space which can be lived in not metaphorically but realistically. Oftentimes as a result, level designers and game designers are working in close tandem with one another, if not being the same entity entirely in the case of small groups. Assuming however that there is a level designer, the responsibility here is largely one of a builder.

The builder takes the architect’s plans, well laid out, and constructs a virtualized space which mimics their essence, and allows for player navigation and exploration through the built space. The responsibility here is to make the space intentional enough to retain the architect’s vision of the space. This can include many different things, including the ability to create textures and design objects to include within the space, as well as understand and map palettes correctly onto different spaces within the game.

The making of a texture is an extraordinarily difficult process that every virtual designer will likely contend with, as a texture is literally a flat polygon that will wrap around a space within the game world to give that space a certain aesthetic sensibility. Textures are prolific in Dark Souls, but are used in every 3D videogame and rendering process, and are an essential part of the art of designing a game’s feel. They are, at a base glance, very simple objects that simply give objects color and feeling, but it is in their multitude that they find success. Just as every stroke becomes an intentional mark on canvas, so to is the placement of textures throughout a game world to give the space a signature sensibility. In Dark Souls, everything, from the plants to the animals to the characters in the game, are little more than wire meshes covered in these textures, and it is usually a large part of the level designer or artist’s job to flesh these out (and similarly so in all 3D games).

Art

While it is inaccurate to say that a game made by many people only has a few artists, it is still fair to say that there are only a few people who are primarily concerned with the game’s art. These are often referred to as the artists or 3D artists in a game’s credits, and they are typically responsible for both conceptual art for the game world as well as some level of construction of textures for 3D objects within the game. Clearly the lines are blurry already, and this is, once again, a primary problem with the videogame, as specialization is often not something readily available. Oftentimes an artist may also be a programmer or a sound designer or any number of other things.

Assuming again that the artist is primarily concerned with just the art however, art in a videogame is an “everything and nothing” kind of reality. The artist may be concerned at one moment with level design or architecture, only to turn around thirty minutes later and have to deal with game design or sound design issues. Art is a precocious implementation within games, as the logical lexicon under which games follow tend to push art outwards, entirely for the purposes of show, rather than an intricate actor within understanding the game in the same manner as the architecture gives the player context. The art within a game thus lives a varied and often underappreciated existence, save but for the few games whose architecture allows overt appreciation.

Game Design

A game designer is an architect of tactility, and of the encounter. This is not how most might describe the game designer. This is a sort consideration of Ian Bogost’s perennial unit, a small piece of the game that allows fundamental storytelling structures and eventually, systems to rise and flourish. When I discuss a videogame as being that of the encounter, I see the encounter as the most fundamental unit of a game, and what game designers spend their time designing. They design the manner in which we feel encounters, the weight of things such as an attack, how much time a dodge technique might take, our ability to interact with the space constructed by the architects, artists, sound designers and writers. They are also typically programmers and are far too focused on attempting to make a game fun in their own definition, without being able to fully flesh out or define the consideration of what it means to do so.

The danger of the game designer is to sacrifice the integrity of the work for a good feeling, for good tactility and response. It is a trap most of the industry is currently mired in. It is also why Dark Souls as a game is lauded so much for its design. Hidetaka Miyazaki, the director of Dark Souls is quoted as saying that Dark Souls, and its predecessor, Demon’s Souls, were “the games I want to create; games I feel users will enjoy. That’s what I do best..” (Official Playstation Magazine March 2011) The danger in making a game is that often the creators refuse to make the game they want to make, striving instead to make a game that somebody else wants. I have not yet met the artist who was completely satisfied in making something they did not want, and this is the sad reality of many game designers and game firms today.

Sound Design

If the Game Designer is the master of tactility, then the sound designer is the master of auditory. The aural tone of the game is represented in its entirety by the sound designer, one of perhaps the few jobs that is typically worked on by a few individuals, and their importance in the process of designing an interactive experience is of utmost importance. Every footstep heard, every auditory conversation is a responsibility of the sound designer, and if the sound designer is good, they will likely be working in close concert with the other designers to capture the tactility and visual presence of the sounds they design.

Dark Souls has some of the most masterful sound design of any videogame, and the particular reason is because the sound adds something of vital importance to the experience. Weight. When something contacts something else, the sounds provided create an enormous sense of weight when interactions occur. Whether it’s dodging or fighting, walking or discussing, the movements carry with them a sense of plausible and visceral weight that is at the heart of why the game is such a joy to play. Sound is an often overlooked actor in videogames, but there is an undeniable quality to it that, if underestimated, can deeply undermine the enjoyment of interactions available.

Writing

Lastly, in our basic architecture of games, there is writing. Writing is another oft overlooked element in a game, and yet text, from the manner in which it is displayed to the manner in which it is spoken, is often a defining factor in our consideration of the game’s world and of its architecture. How things are said, how often, the manner in which characters carry themselves, is all reflected in writing, and offers a great deal of insight that cannot be done with construction alone. We are beings with a deep desire to communicate for the purposes of understanding, and writing in a game offers the player an ability to penetrate that depth.

The key aspect towards text is largely a process intertwined with the entirety of the game. The text often gives structure to larger, overarching narratives, gives us a look into the game world’s character on a level instantly related to personhood, and if written well, allows the player to become fascinated with the world in which they’re interacting. Fascination is vital to suspension of disbelief, and creates a suitable environment for the player to, beyond being immersed, to lose themselves in. To find themselves thinking about all the little possibilities the small shards of text available to the player might mean, if only given greater context. Yet the greater context is fascinatingly right before them, in the architecture and other designs, only requiring enough digging to find it. If it is the architect’s job to leave the player immersed in the game environment, I believe that it is the writer’s job to make them fascinated by it, to give them words with which to consider the world’s mythology.

The Architecture of Dark Souls

These are the various parts of a game, and the manners in which they might be efficiently designed or discussed, but by themselves they largely serve as descriptors, little more than fodder to attempt to describe games and their approaches on the whole. However, the intention of the discussion herein is intended to be about the architecture of Dark Souls specifically, and to that end I have created a series of short clips discussing what I believe are some of the important matters in Dark Souls. Provided at the bottom of this page is also a full architectural discourse of the first level of Dark Souls, done to the best of my meager ability.

Dark Souls Architecture and Processing

This first clip provides a number of insights into the game world of Dark Souls, the first of which is the choice of music in the particular place in which the character is at, and how it is dynamically changing. The second of which is an observation about the fact that despite the player existing within the game world, the game world has described limits unto the player which the player must follow as general rules while playing the game. Another is a vision of the architecture itself and what the designer intends when showing us such architecture and under such structured conditions.

This area is the first area of the Dark Souls game after the tutorial area, also known as the Undead Asylum, a place where the souls of the undead are kept to await an unknown judgment. Escaping the asylum, you enter the area via a large crow that carries you to the place shown in the video, the Firelink Shrine. The shrine is dilapidated, grass is growing around it everywhere, and all around us we can see signs of a world not quite right, yet we are only allowed to wonder, “How can a so seemingly splendid kingdom have ended up in such a state?” It is a driving question that the architecture, through the use of sights and sounds, and unfortunately the imperceptible, indescribable feeling of the interactions available that drives us thus.

The architecture is gothic, no trappings of the baroque adorning any walls, no fancy recompense for the breadth with which we can see, and yet there is a fascinating architecture all around us, a mysterious aura of sadness that seems to permeate the space entirely. Is it a space we are curious to explore, or a space so uncertain that we simply do not wish to be immersed within it, so as to avoid drowning in its wilting? Despite the uneasiness, the game presses us forward with its architecture, guiding us along various paths to explore using the decaying arcs to leads us through the halls of a once venerable shrine, eventually leading us to our first encounters and enemies with which we are both familiar and unfamiliar.

Dark Souls Architecture and Encounters

The enemy encounter is perhaps the most fundamental unit to Dark Souls game design, as it is what the player will be doing for the majority the game, and understanding the design is of utmost importance in attempting to understand how there occurs an interplay between the game design, level design, and architectural design within Dark Souls.

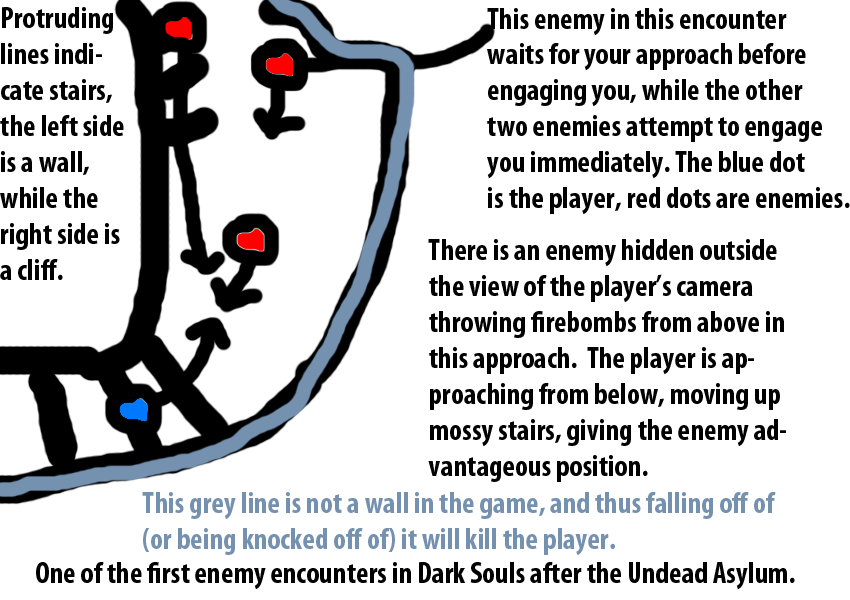

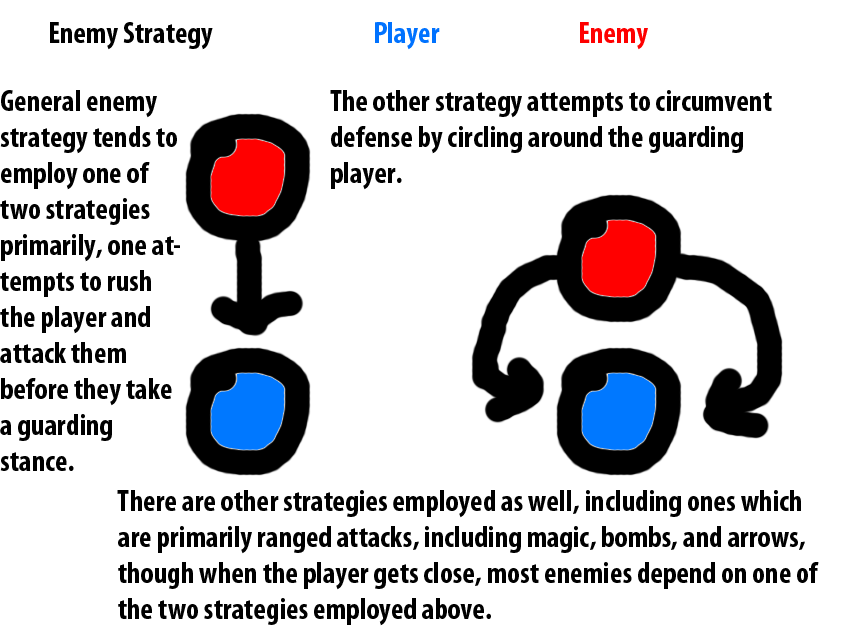

In the case of the encounter here, we see that enemies and the player have a variety of approaches in which they may take in order to attempt to grapple with the design. The player is given more tools, while the enemy is typically given numbers or superiority of position to create a more dynamic world by forcing the player into interactions that require conscientious decisions about who, what, when, why, and how they will interact. The tools in the case of the player are perhaps most formally understood as attacks and defense. Stamina is the green gauge in the upper left-hand corner and is the centerpiece for performance of any specialized move, including attacking. The dodge is a unique defensive move that gives the player a certain amount of invulnerability to harm, as well as changing the player’s position greatly in relation to opponents, however it requires a certain amount of stamina to perform. A shield or other objects can act as a defense, sometimes limited based on the type of offense employed, though blocking both takes stamina to do and while the player actively has their guard up, stamina recovery is greatly slowed. The player is also given the ability to target enemies and determine the order in which they will interact with aggressors. Finally, the player can also employ a variety of methods with which they can attack, including spells, backstabs, charges, ripostes, and other abilities. Most attacks are based on the type of weapon equipped and the player’s proficiency with the weapon, as well as necessary character statistics needed to wield the weapon properly. If a player does not have proper statistics, while any weapon may be wielded, it will be wield inefficiently and largely be a burden rather than an asset to use until the proper statistical necessities are met. Magic without the proper statistics cannot be used at all. Enemies are actually very much the same. They have statistics, a stamina gauge, and health, as well as multiple abilities and attacks, just as the player does (see the image on enemy strategy). Little of this is overtly displayed, except in boss battles, which are an architectural form in games unto themselves.

In a sense then, the encounter is somewhat a product of understanding the necessary timings in battle, at least as the enemy encounter applies in Dark Souls. The architecture of the encounter here however is unique. What we see is that the enemy is encountering the player from an advantageous position, from high up, and they are pushing us against a sheer cliff. In the encounter, we see the brilliant interplay between the game design, the level design, and the architecture. The game design forces the enemies towards us, pushing the player towards death, forcing the player to take position somewhere further along, forcing the player to push forward. Without the architecture and the threat of death the cliff provides, a great deal of the tension in the encounter would be lost. In Dark Souls, the architecture often speaks in a dangerous manner, where the environment is alive in the sense that the environment is something the player must constantly take note of, lest they irrevocably harm themselves. Yet at the same time, it is also something the player can navigate and find appreciation in, if they are, despite the danger, willing to take the time to carefully observe.

By irrevocably harm, I mean players lose their “souls.” In the game, dying will simply respawn the player at the last bonfire they rested at, but without any souls or humanity. Souls are effectively a currency gained by fighting enemies, and humanity is gained incrementally through how long the player has been playing without having died. Humanity is only regained over time or through items, and thus it is a resource even rarer than souls, which can be recovered by battling enemies. Uniquely, in this game when you die you have a chance to regain your lost currency (your souls and your humanity) by managing to get back to the place where you died and recover your souls. It is a product of a great deal of the game’s tension, where a great deal of loss can occur with only a few mistakes.

Dark Souls Architecture and Boss Encounters

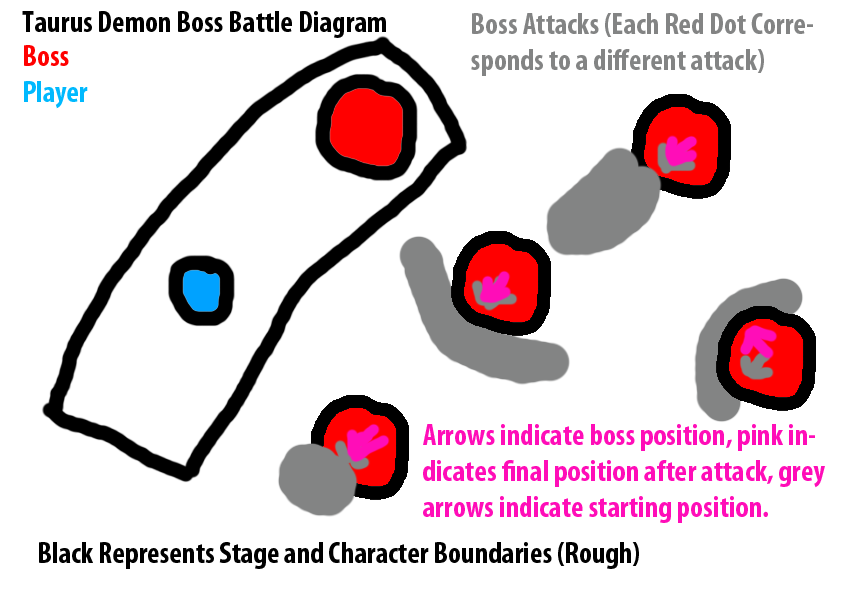

The first boss battle in the game proper of Dark Souls is with a named enemy called the Taurus Demon. A representative Minotaur-like demon with bull-like strength, he represents a certain mythology of the labyrinth, the player exploring the area below the demon to meet the monster. The architecture here, as with many boss encounters, plays a vital role in how the player can interact with the enemy.

The architecture here is a narrow space, barely large enough for the Taurus Demon to navigate through, making it difficult to get close to the enemy without having to worry about the boss’s weapon’s large damage and long reach. To circumvent the architecture, the player must carefully circle around the enemy and rely on blocking attacks and responding with correct timing. To another degree, the fight can be avoided to a certain by using magic, such as the Pyromancy employed in the video. Despite the use however, it was still necessary to approach and finish the fight with a few final attacks directly to the enemy, and because of a boss’s typically high health, it often becomes necessary to approach them in a manner in which they have a degree of advantage.

The architecture in the fight itself is also interesting, in that unlike many sections previous, the gothic buttresses are particularly prominent, as if to attempt to lull you into a belief that if you are knocked back by the demon, you will still be safe. In a sense it is true, but it is also somewhat deceptive. The Taurus Demon can actually knock the player far enough that they can be sent over the edge of the buttress, and there is a section in the wall which there are none, making it a particularly dangerous place in which to attempt to fight him. Though the Taurus Demon will not lure you to it and attempt to exploit it, the fact that it is there belies how intentionally constructed the space is with a penchant for adding a dangerous edge to every interaction. Even the spaces which seem safe are often deceptive.

Dark Souls Architecture, Non-Player Characters, and Verticality

The non-player characters within Dark Souls are a unique breed indeed. Each of them is intentionally placed, each of them has their own motives for helping you, and none of them are necessarily your friend. They all seemingly stand to gain something from your participation in whatever decisions you decide to make or not make towards them, and all of these decisions greatly affect the game world as well as interactions available both within and from the online network which makes up the online portion of the game’s space. Verticality is also an interesting aspect which Dark Souls has designed into itself, similar to its predecessor Demon’s Souls, it is designed in a manner which intentionally shows us the landscape as we explore it, forcing us into views to take in, in some sense, the lost grandeur of the space the player virtually inhabits.

The non-player character in Solaire of Astora is a fascinating one. Though he seems to want to help the player, he seems at least slightly off, if not really off-kilter. You get a distinct sense that something he has lost is both barely keeping him in place, and at the same time slowly forcing him into madness. Perhaps his own conception of the world are part of what bring it on, his desire to be bathed in what he calls the luminescence of the sun. Perhaps he lost something and is holding on to a memory of what that once was. In any case, the fact that he gives us something shows that he intends something towards the player, despite the player not really formally knowing what. It is not so much the fact that he believes that individuals should work together in a hostile world that is unnerving nearly so much as the manner in which he states it. It is an odd feeling, despite our ability to agree that help would likely be appreciated. The player leaves Solaire to find the first checkpoint, a shortcut that begins to display the deep verticality embedded within the game, and how connected everything within the game world is.

Verticality in Dark Souls is similar to Demon’s Souls, in that unlocking certain waypoints, in the case in the video, a ladder, allows the player quick access to an entirely new section of the game, and yet it was always only a small space away from the player. The fact that there exists a sort of vertical layering effect within the game is another point of its brilliance architecturally. Despite the difficulty with which constructing such a world entails, it nevertheless follows the idea of the game, one which is fascinated with going higher and higher into the heavens, and deeper and deeper into the depths of hell. The idea is intentional, one which strives for the conception of a space that keeps going virtually, despite our honest understanding that all game worlds, including this one, have limits. Because the verticality is so deep-seeded however, both descent and ascent are able to take hold as key thoughts in our minds while navigating the architecture of the game world, and they are made intentionally obvious so that the player is constantly made aware of the verticality of their surroundings. In a certain sense, it begs the question of how long we will stare, either into the sun or into the abyss, and such a question achieved through virtualization of a vertical architecture is a great feat.

Closing Thoughts

The architecture of Dark Souls is an exceptional creation of what is clearly a great deal of thought about how the designer wanted the player to view the design. The verticality, the dilapidated surroundings, the sparse characters and even sparser enemies are all intended to show that the world was a space with its own lived-in mythology. They build conceptions upon conceptions of the world, allowing the player to only peek in and gather bits and pieces, allowing for a rich discourse as much about the possibility of what the space might intend as much as the overt telling of the story, of what actually occured, at one point in this space to end up in such a terrible condition. It is through our ability to understand that we, in small pierce the darkness, and yet find that by attempting to do so, we only end up ever more consumed by it. Oftentimes, it is the boundless desire for knowledge and power that is as dangerous as what lies within those constructs. A common, human greed to know betrays us all at some point, and oftentimes leaves us more battered than we once were. These are the kinds of worlds Demon’s Souls and, Dark Souls, are. Worlds filled with a richness that belies a similarly great darkness. The architecture, then, is a reflection on such greatness, on what comes to pass for all once-great kingdoms.

Architectural Discussion of Dark Souls

Bibliography

Join the conversation

[…] design, and the multisensory spatial “encounter” in game design. You can find his paper here; it includes videos in which he narrates his spatial experience in playing “Dark […]

[…] design, and the multisensory spatial “encounter” in game design. You can find his paper here; it includes videos in which he narrates his spatial experience in playing “Dark […]

[…] design, and the multisensory spatial “encounter” in game design. You can find his paper here; it includes videos in which he narrates his spatial experience in playing “Dark […]