To some degree, all video games are dream worlds. We're sucked into their backwards logic, their obtuse rules and their baffling stories and design, and only when we leave them do we return to any sort of reality. Few games understand this, instead offering us a version of reality that seems real when we're playing the game, only to cause the player to think afterwards, "well, that didn't make much sense."

Creating a dream world that is consistent in its logic is perhaps the most noble of video gaming's aims, but it needn't be restricted to one type of game, one genre or one style. Link's Awakening, originally released on the Game Boy and then later on the Game Boy Colour in 1998 as Link's Awakening DX (the version I played), is a game that quite clearly understands the fundamentals behind the dream-logic of video games, of Zelda's and indeed of Nintendo's entire past. This isn't just because Link's Awakening takes place in a literal dream world – it goes far deeper than that.

For all of my quasi-intellectual prattling here, the thing that Link's Awakening does so much better than almost any video game I've ever played is having fun with its own conventions. This is a handheld Link to the Past in everything but name only, but it's more aware of its mechanics and template than A Link to the Past ever was, coming across as either a knowing satire of Nintendo's franchises or even as an outright parody of the Zelda franchise. Nintendo applied a freewheeling design philosophy to Link's Awakening that saw them include everything from cameo appearances by Mario, Kirby, Yoshi and other, more obscure characters from Nintendo's past, to a devilishly loopy script that manages to squeeze in all sorts of Zelda conventions while simultaneously deflating them in the most hilarious ways possible.

The game is an experiment in metanarrative, meaning that both it and the player are constantly aware that they're playing a video game. And despite what would initially seem like something meant to keep the player at bay, instead, it draws the player into the game even more. The Zelda series gained a lot of its charm and wit from this game, creating for the first time a cast of quirky or outright weird characters that give the game, well, character.

The Zelda series has, to some degree, always seemed to exist as its own separate entity, unaffected by the changes in video gaming at large, and while that's still true here, the first signs of pop culture invading the Zelda franchise occurs here. Apparently, many of the staff members, including Kensuke Tanabe (who would go on to become Nintendo's manager of second-party operations, producing games like Metroid Prime and Donkey Kong Country Returns), were enamoured with David Lynch's seminal television series, Twin Peaks. While the epic template of Zelda and the uncomfortably strange and exacting Twin Peaks seem like strange bedfellows, the idea of a town being filled with shady, untrustworthy, yet quirky and lovable characters, is something that binds the two series together. For a 1993 Game Boy game, Link's Awakening has a surprising amount of depth in its script, something that has the player simultaneously laughing out loud and feeling a kind of dull ache from the game's touching narrative conceit.

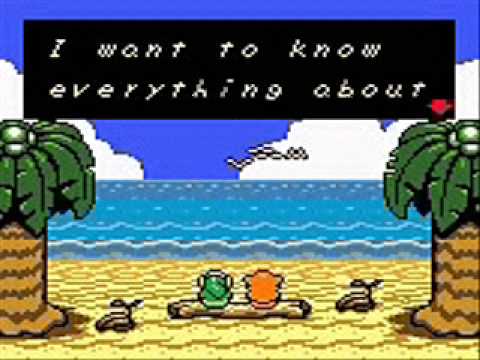

Basically, the game's narrative gets grafted onto the classic Zelda structure: Link arrives on Koholint Island, far, far away from the land of Hyrule, after his ship hits a massive storm. Washing up on the beach, Link's not out to save the world, but merely to get himself off the island. A mysterious owl informs Link that to do this, he has to awaken the sleeping Wind Fish, who will help him escape. Later in the game, it's revealed that Koholint Island and everything on it is within Link's sleeping imagination, and everything, including the people he meets, are wiped away when the Wind Fish is finally awoken. And before the Wind Fish can wake from its slumber, Link has to defeat his "nightmares," which take the form of bosses.

Like I said, this plays out in large part like A Link to the Past, and no wonder, as Link's Awakening originally started as a port of that game to the Game Boy before the development team went wild and started chucking in as many things as they could into the game. While the storyline and characters and situations are refreshingly "fuck it, whatever," the gameplay is as sharp as it's ever been – scratch that, it's the best 2D Zelda gameplay yet seen. A variety of new tools (such as the eventual series mainstay the Hookshot) make playing the game's many dungeons a treat, and the puzzles and dungeon layout are the most devilish the series has ever seen.

That makes Link's Awakening a damned hard game, not only because the enemies are especially daunting, but because the game demands that you figure out not only its various temples, but also the entire world map, requiring a knowledge of every event and every place that you could possibly go to. This engenders quite a lot of exploration, which is always rewarding (especially in a game as detailed as this one), but it also leads to a bit of frustration, as the solutions to things are always about two lateral steps sideways from what you think the solution is.

Koholint Island may never return from Link's dream world, but while we're there, the player is actually given great insight into the inner workings of Link's mind. The whole game, without stating so explicitly, is a run through Link's psyche and his fears. Luckily, though, the game never gets bogged down in any sort of po-faced seriousness, instead reveling in the silliness that the clearly-having-too-much-fun development team (led by Miyamoto's right-hand man, Takashi Tezuka) provides. Link's Awakening is a refreshing change of pace, a superlative 2D Zelda experience, and one of Nintendo's greatest games; but more than that, it understands video games, it pokes fun at them and makes Link's Awakening a self-reflexive experience that's far more accomplished than it's "side-story dream world" premise might make one think.